Partly on the wise urging of a reader here, I reread Vineland a month or so ago. My original go at it however many years ago was a bit juvenile. Gravity’s Rainbow was my first Pynchon, and this followed hot on its contrails. Predictably, I was craving paranoid pyrotechnics and wild world-historic tangents and wound up sort of bemused by Vineland‘s zany family narrative. I was also a teenager at the time. If you’ve read any of my previous posts here on Vineland themes, you may have noticed a certain fuzziness on my part around plot and character. Forgive me—I just couldn’t remember the thing.

This time round, I found myself much more receptive to Vineland‘s post-hippie charms. The narration is playful almost to a fault—I could see a reader turned off by the near wall-to-wall zaniness—but for me, Pynchon sticks it; it’s his most laugh out loud concoction by a good margin. At the same time though, Vineland gives us Pynchon’s signature yearning for a better, more open history, or his mourning of the compromised, always already foreclosed history we’ve found ourselves living with, in its clearest form to this point in his career. And sure, the plot is sometimes muddy as hell—the whole ninjette section left me a little nonplussed. But the book is also achingly beautiful at points. Zoyd waking on the Greyhound to baby Prairie talking “in a very quiet voice” to the redwoods “as they passed one by one” (p. 315) sticks with me, just for example.

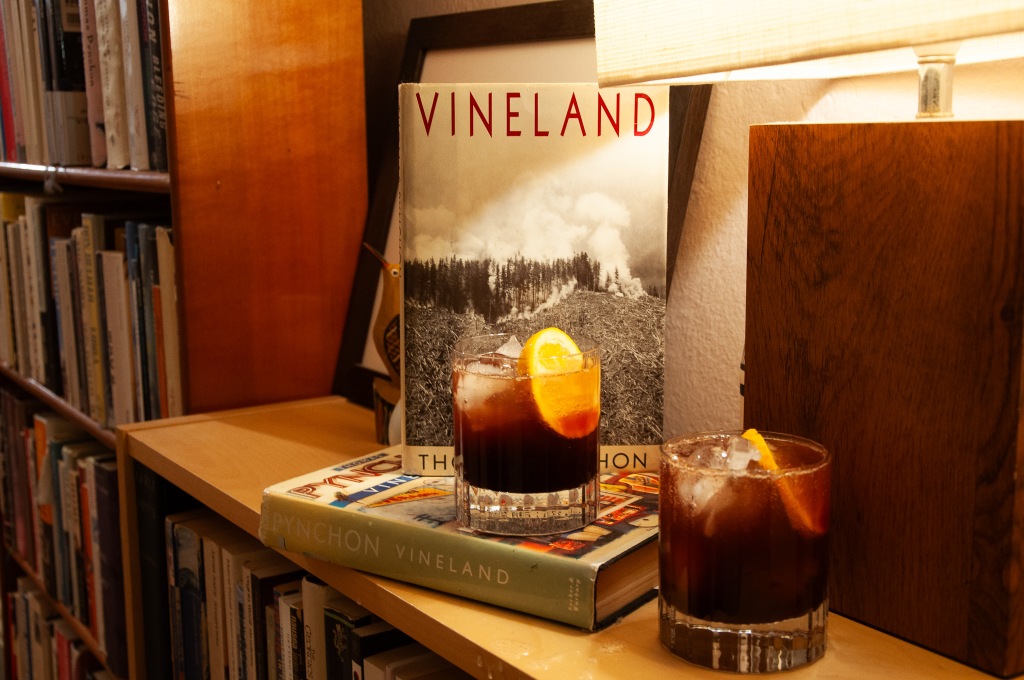

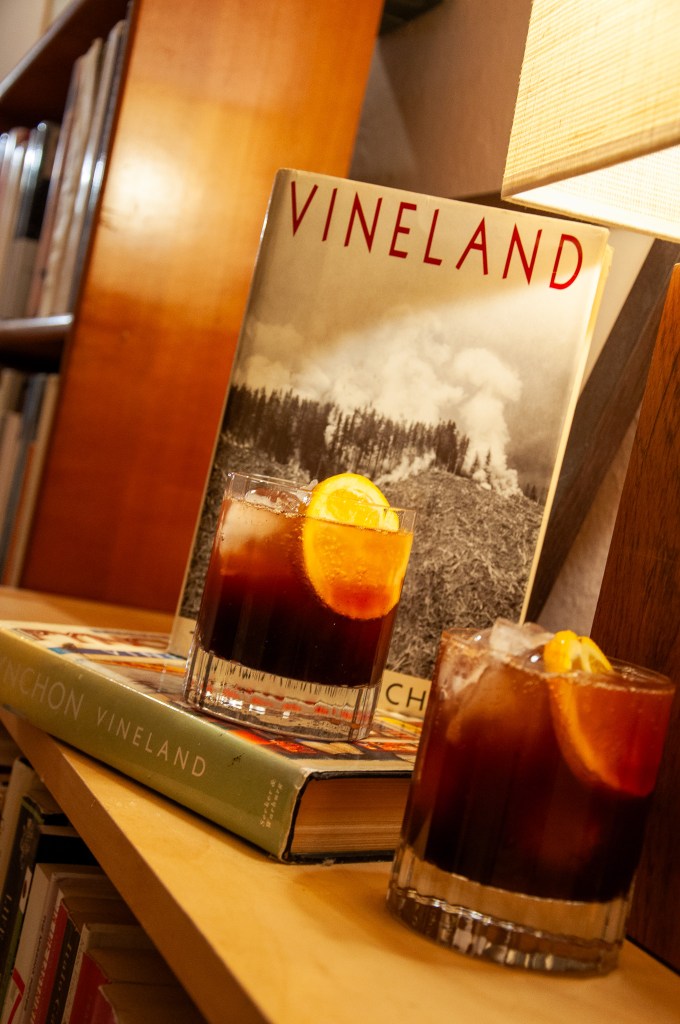

From this more familiar vantage then, let’s knock off a Vineland drink. Frenesi’s stuck more compromised than anyone, manoeuvring her maths-professor turned guru boyfriend Weed Atmann into sight of a gun at the behest of her other boyfriend, notorious cockheaded lawman Brock Vond. (It’s that same gun episode our characters find escape from around the imaginary Chenin Blanc we sipped not long ago.)

Weed was wearing sandals with argyle socks, a departure from the hip that Frenesi had just begun to find endearing, and drinking one after the other spritzers of a fortified demographic wine, analagous to Night Train or Annie Green Springs, but targeted to the bario, known as Pancho Bandido.

Vineland, p. 243.

Night Train was a Gallo-produced flavoured fortified wine spritzer, cheap, sweet, and boozy. According to a rundown from the ever reliable Drunkard Magazine, Gallo had a range of similar products targeting different segments at the time, including a “Cherokee” wine marketed not-so successfully at First Nations Americans. A Time article in 1971 described these “pop wines” as adding “a pleasant extra dimension to the effects of pot”, appropriately enough for our friend Weed. They’ve all more or less fizzled out by now, though Annie Green Springs seems to be perpetually on the verge of relaunch, and it appears one can come by Night Train in Nigeria (hook me up if you’re heading through that way). Pancho Bandido (tr. “hot-dog bandit”!) is fictional, but not at all out of line with the sort of thing Gallo and co were trying on at the time.

As boozy wine spritzers aren’t flooding bottle shop bottom shelves these days, I’ve just mixed my own with what I had around. Ingredients were

- a shot of some port but then the bottle ran out so I also added:

- a shot of Pedro Ximinez;

- a shot of lemon juice;

- half a shot of simple syrup;

- a dash or two of old fashioned bitters;

- enough soda water to top up the glass.

The end result is sweet and easy; cinammon and prune from the PX come through strong and Christmas-cakey, but the sugar and acid and fizz keeps things smashable. Smashable, if it’s not too glib, as Weed and PR³ and 24fps and the whole sixties counter-culture turned out to be in the face of the DEA and the FBI and the CIA and capital and real estate and television and the whole Them-complex. No no okay, that is too glib. Read Vineland again! It’s a good time!