I remember clearly the moment I reached page 376 of my first reading of Against the Day. I’d already been moonlighting as Drunk Pynchon here for a few years, just with a big “Coming Soon” sign plastered in place of the AtD list (or actually, it originally said “coming less soon”; I was pretty intimidated by the thing). Against the Day, as well as an alternately rollicking and unsettling ride, was feeling like an incredible gift to the project—by page 376, I’d already logged more than 40 drinks. And then, things really got good. We start with a hint, a glimpse caught among a minor Slothrop’s-Desk of sights by Frank Traverse as his train heads into Guanajuato:

All along the passage, through the mesquite, beneath the soaring hawks of the Sierra Madre, arroyos, piles of ore tailings, cottonwoods, through black fields, where tlachiqueros brought sheepskins slung across their backs full of fresh maguey juice to be fermented, and campesinos in white lined the right-of-way, some packing weapons, some watching empty-handed the train’s simple passage, “expressionless,” as gringos liked to say, beneath their hatbrims, waiting, for a feast day to dawn, a decisive message to arrive from the Capital, or Christ to return, or depart, for good.

Against the Day, p. 376.

Well I was immediately off googling (the AtD wiki was never far from hand). Tlachiqueros, I found, are workers who extract sap from the maguey (or agave) plant in order to make a drink called pulque.

I Wikipediaed feverishly, devouring new pulque knowledge: Pulque is agave sap, fermented to around beer strength. It’s been made in Central Mexico since pre-Colombian times. The Aztecs regarded it as sacred and forbade consumption of more than one drink, lest the drinker fall under the spell of Cenzon Totochtin (the “four hundred rabbits”). Pulque doesn’t keep at all, and can really only be found in central Mexico, where it’s still made by various small producers. It was described as tasting funky and tart and having a viscous, slimy, almost mucous-like texture.

As you know, I generally like to keep things a bit more highbrow around here, but I think the escalating excitement brought on in me by this series of pulque revelations is best illustrated by the following bespoke meme:

A pilgrimage was clearly in order. Seven plus years later, I’ve managed it.

My first taste of pulque came at Pulqueria Los Insurgentes, an “expendio de pulques finos” in Roma Norte (a suburb something like the Williamsburg, NY or Collingwood, VIC of Mexico City). We wandered in there on our first night in Mexico, a quiet Wednesday evening. A couple of other drinkers were dotted around the place with 1 L tankards of milky, pastel-coloured liquid before them. The bartender said something to me about pulques and I responded “si!”, hoping I hadn’t just ordered us a litre each. (I had in mind my past experience with kumis—another exotic opaque white Pynchonian beverage—which on my first tasting I struggled to get through 150 mL of). Happily, he brought us four shot glass tasters. The first was the “natural” straight pulque; the other three were “curados,” or flavoured pulques. We sipped through and found them all suprisingly tasty. Mildly sweet, fruity, a little tart, with a mild kombucha-like funk in the background. Thick like a smoothie, and not even sort of snotty. My travelling companion (as lovely as she is tolerant, having travelled to the other side of the world with me for this moment) ordered a 370 mL of the guava curado, and I got the light pink one, the Spanish description of which’s ingredients had eluded me, but which seemed to involve oats, possibly nuts, and some kind of red fruit. They were good!

Our next pulque experience was a little more intense. One of the more legendary CDMX pulquerias is Pulqueria Duelistas in the centre of town. We arrived there Friday night to find the place raucous and absolutely packed, but were given a couple of seats to squeeze into at the end of a table with four somewhat sodden-looking middle-aged señors. I ordered a cup of the natural, ready, I thought, for the unadulterated pulque experience.

Meanwhile, our table companions engaged us in vigorous cross-cultural dialogue. The man next to me did not appear to speak a word of English. I’ve been doing duolingo Spanish for three months. You would not think this combination would provide us with a promising foundation for an hour’s conversation. Nevertheless, he monologued at me continuously en español the entire time we were there. Occasionally I would tell him “no entiendo” or “no hablo espanol,” but he didn’t seem to see how this was relevant. Sometimes I would nod and say “si, si,” hoping I wasn’t agreeing with anything too egregious. Now and then, he would get worked up, as if I’d agreed with the wrong sentence, and his friends would lean across and try to placate him. I got the approximate idea at one point that he was asking me my thoughts about immigrants; let’s assume his were very positive. One thing I did grasp was that he thought we should move to Mexico. Duolingo perhaps should incorporate more listening activities where the speaker is wildly drunk; I’m sure I can’t have been far off keeping up.

My girlfriend had scored a much more English-speaking, though no less drunk, seat neighbour. He spoke at her with more or less the same intensity my friend spoke at me, though at least she could tell what he was saying. He was curious as to how we liked pulque, and Mexico in general. He told us the three of them were lawyers and old friends. (The third amigo sat the whole time smiling bemusedly, drinking and saying nothing, while his friends jabbered at us in their respective languages).

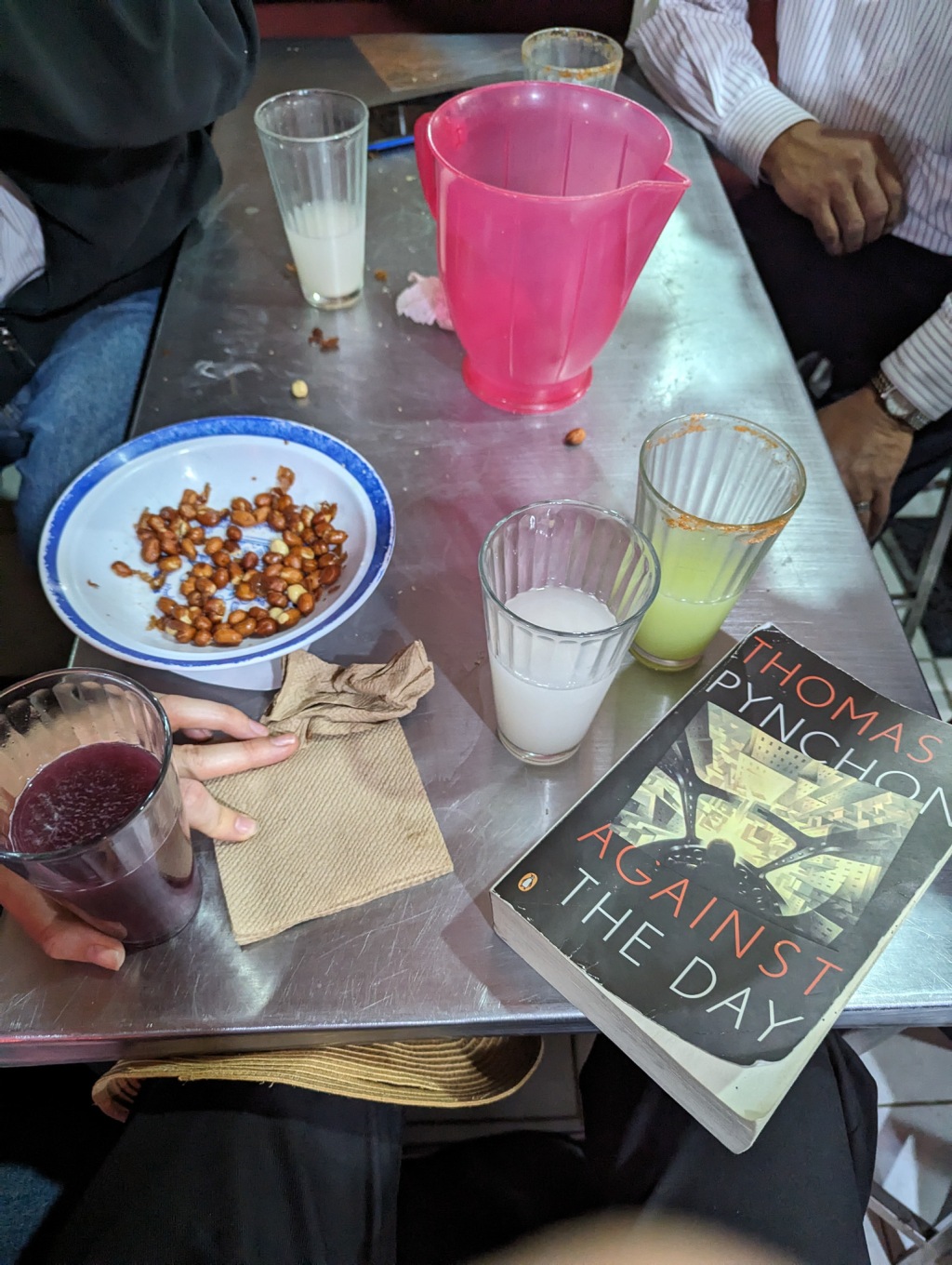

Without us realising, they bought us a round, a big plastic jug of natural for the table. The bartender told us they were drunk (no!); they’d been there for four hours. I got out my travel-ready extra lightweight paperback Against the Day at one point to take a surreptitious photo or two. My amigo grabbed the book and started thumping the cover repeatedly in emphasis of the key points in a new twist in his monologue. I have no idea if he was declaring that Pynchon misunderstood Mexico, or that he preferred the work of William Gaddis, or that reading was for wimps. I did catch something about Porfirio Diaz in there at one point. The English speaker laughed uproariously but showed no interest in translating. Whatever it was, the sight of AtD inspired some strong feelings. I got one scuzzy snap and put the book away.

The bar this whole time was periodically erupting into chanting and song. The place was hectic. Adding to the intensity, the walls and ceilings were painted all over in sort of acid-Aztec designs. It really was one of the more out there drinking experiences of my life. After spending a reasonable amount of time at posh Roma Norte cafes and bars, Duelistas felt like a different Mexico entirely, like we had slipped into the other Mesoamerican image glimmering in the Iceland spar.

And I’ve gotten entirely distracted from the pulque itself! The natural at Duelistas was a bit more intense than what we sampled at Insurgentes. It had the unnerving habit of forming long tenacious gooey strings between mouth and glass whenever I tried to take a sip. This seemed to be partly an issue of technique on my part, as I didn’t notice anyone else trailing goo like I was. I tried to add a sort of twist to my sip to break the string. Our friends wanted to “salut” afresh with more or less every sip anyone took, so they must not have been too put off by my approach. Texture aside, it was pretty enjoyable stuff. Funkier than the Insurgentes product, but still a little sweet, yogurty, and pleasantly vegetal. We also had some blackberry curados that were sweet tasty easy drinking.

Back in the book, Frank gets a job doing amalgamation in Guanajuato:

He and Ewball had soon settled in to the cantina life, the only uncomfortable part being what Frank imagined were strange looks he would get every now and then, as if people thought they recognized him, though it could have been all the pulque or the absence of sleep. When he did sleep, he dreamed short, intense dreams nearly always about Deuce Kindred.

Against the Day, pp. 376–77.

Pulque’s in the picture again when Frank eventually finds Duece’s running-mate Sloat:

It came to pass that one day Frank rode in out of some irrigated cotteon fields at the edge of the Bolsón de Mapimí, down the daylit single street of a little pueblo whose name he would soon forget, walked into a particular cantina as if he’d been a regular for years (adobe walls, perpetual 4:00 A.M. gloom, abiding fumes of pulque in the room, no Budweiser Little Big Horn panoramas here, no, instead some crumbling mural of the ancient Aztec foundation story of the eagle and the serpent, here perversely showing the snake coiled around the eagle and just about to dispatch it […] and found there right in front of him, sitting sloched and puffy-faced and as if waiting, the no-longer elusive Sloat Fresno […]

Against the Day, p. 395

Both draw pistols, “duelistas” for real, but Frank dispatches Sloat, serpent on eagle, Sloat’s blood slapping “across the ancient soiling of the pulqueria floor,” (p. 395).

My final rendezvous with pulque was supposed to be a visit to an agave farm in Tlaxcala. In the days after our visit to Duelistas though, I became increasingly subsumed by the effects of a mysterious Mexican flu. Indeed, I began to feel I was more mucous than man. Was the pulque to blame, gooey strings and all? Was I to join Duece Kindred in meeting my end thanks to a visit to a pulqueria?

No, I was fine. While the agave farm eluded me, I found solace in the abundance of agave plants dotting my path elsewhere. We found some good ones around, on the streets on Mexico City, around the pyramids of Tenotihuacan, even in San Francisco on the way home.

I’m currently halfway through a reread of Against the Day, having not managed to polish the whole thing off while in Mexico. I believe pulque reappears once more ahead of my current position. Late in the book, Frank is back in Mexico, where he’s been fighting in the Mexican revolution. He takes peyote with someone called El Espinero (my memory of these sections will benefit greatly from finishing this reread) and hallucinates, amoung other things, “strings of mules […] bearing also the maguey stems harvested by the tlachiqueros,” (p. 925).

Even having drank several more-or-less physical glasses of the stuff, pulque does still seem shrouded for me in a hallucinatory aura, flickering between the real and imaginary axes. Like Frank, the tlachiqueros may long shadow my dreams.